Women’s Boxing Circa 2017

Amanda Serrano defending title against Calixita Silgado, July 30, 2016. Photo Credit: Behind The Gloves

While women’s boxing has been around since “modern” boxing began in the 1720s, its place in American sports consciousness began with a trickle in the 1950s and grew to a steady flow by the late 1990s before petering back in the late 2000s.

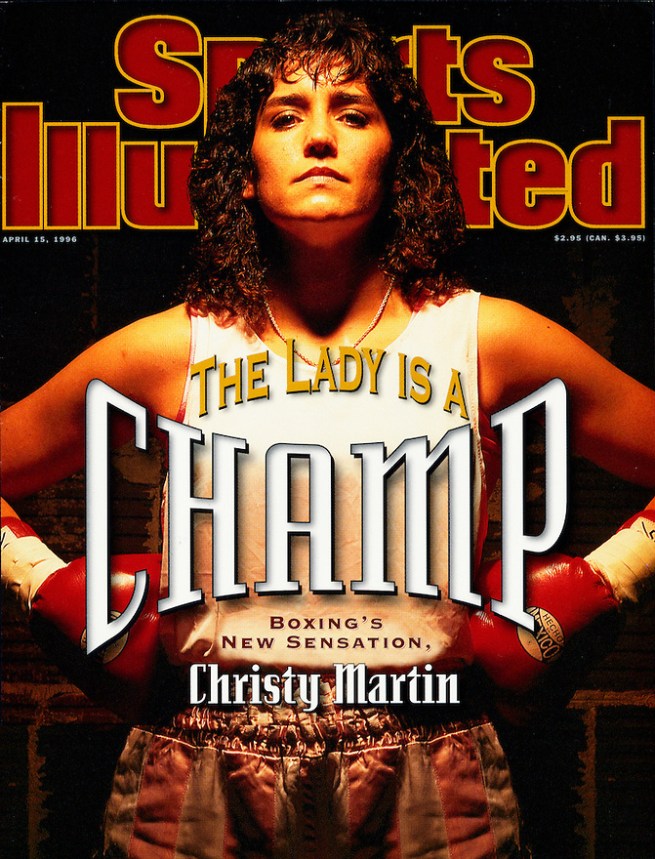

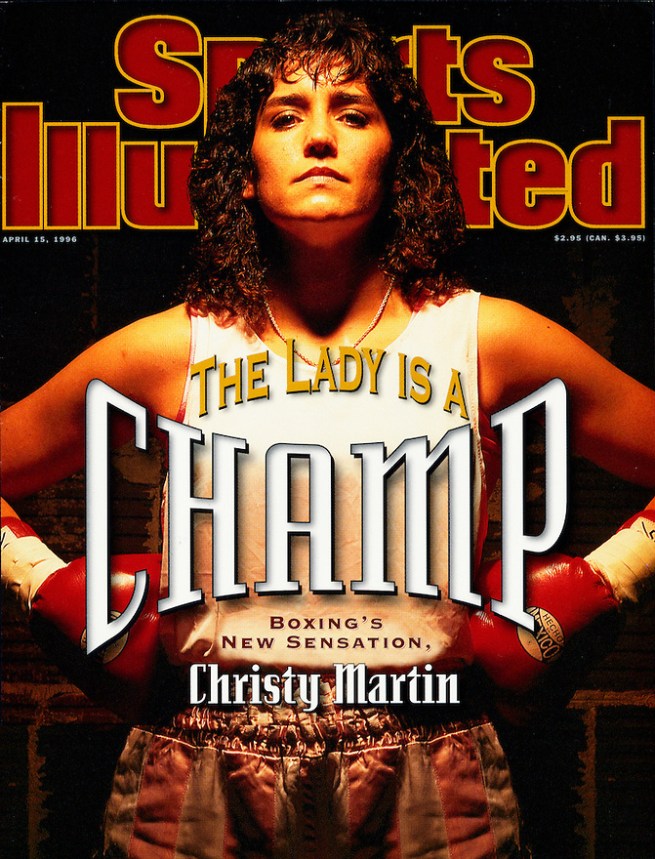

Boxer Christy Martin’s bout against Irish fighter Deirdre Gogarty on the undercard of a Mike Tyson pay-per-view championship in 1996, put women’s boxing on the “map.” Not two weeks later Martin was on the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine in her characteristic pink boxing attire, and for the likes of boxing impresarios Don King and Bob Arum, it was a race to find other female fighters to add to the undercard of boxing bouts.

Such fighters as Lucia Rijker and Mia St. John, while not household names by any means, were becoming known in the boxing community—and even sported decent pay days that could be numbered in the thousands rather than the hundreds. At the same time, women’s boxing became a sanctioned amateur sport leading to the development of a national team in the late 1990s. The beginnings of international amateur competition began in 2001 coinciding with the legalization of the sport in countries across the world.

In the United States, the entry of Mohammad Ali’s daughter Leila Ali along with other boxing “daughters” such as Jacqui Frazier-Lyde, thrust the sport into the realm of popular culture including covers of TV Guide and a myriad of talk show appearances. With Leila Ali’s ascendency, however, other American female boxers of the period such as Ann Wolfe, Belinda Laracuente, and Layla McCarter, could not find traction on pay-per-view cards or on cable, despite excellent boxing skills (frankly much better than Ali’s) and by 2010, it was hard if not impossible to find female boxing on American television.

At the same time, internationally at least, women’s boxing was in an ascendency in such places as Mexico, Argentina, South Korea, and Japan, not only with opportunities for decent fights, but reasonable paydays, and most importantly, fights which were broadcast on television—and continue to be to this day, with female bouts routinely marketed as the “main event.”

International amateur women’s boxing was also on the ascendency culminating in the inclusion of women’s boxing as an Olympic sport in the 2012 Games in London. For such European fighters as Ireland’s Katie Taylor and England’s Nicola Adams, winning gold medals became very important national achievements leading to endorsements and other opportunities, not the least of which was recognition of their place in history and as role models for younger women and girls. For America’s boxing phenomenon, Claressa Shields, who at 17 was the first American female to ever win a gold medal for boxing, the usual promise of Olympic gold endorsements never appeared, and any sense that the inclusion of women’s boxing in the Olympics would perhaps enable a resurgence of the sport in the United States did not materialize. The other American female medalist who won a bronze in the 2012 Games, Marlen Esparza, had slightly better luck in winning endorsements, with adds for Coca Cola and Cover Girl, and a certain amount of traction in the Hispanic community, but otherwise, her Bronze had little effect on the sport as a whole.

In fact, women’s professional boxing has remained virtually absent from the airways in the United States with very, very few exceptions over the past eight years—and in fact, with respect to national exposure, i.e., network television or nationally televised cable boxing programs (ESPN, et al), such instances can be counted on one hand between 2012 and 2016.

The exceptions have been certain local fight cards such as New York City-based promoter DiBella Entertainment’s Broadway Boxing series, which have promoted and televised female bouts on local cable television channels. The same was true of a few of boxing champion Holly Holm’s fights in her local New Mexico market.

Some women’s bouts are also available live from time to time on US or internationally based internet pay channels at anywhere from $10 to $50 a pop. Otherwise, the only other means of watching female bouts has been on YouTube and other video services, where promoters may upload fights days after the bout. Viewers have also come to rely on uploads from fans that record all or some portions of female bouts. The clips are uploaded to social media sites such as Twitter, Instagram and now Facebook Live, in addition to YouTube, Vimeo, et al. Additionally, it is possible to watch international female professional boxing bouts via satellite television. International amateur female boxing tournaments are also available on occasion for website viewing, and certainly women’s boxing in the 2012 and 2016 games were available on the NBC Sports website, albeit, after much searching.

Three of the handful of professional female bouts broadcast since the 2012 London Games included, boxing champion Amanda “The Real Deal” Serrano’s six-round bout which was televised on a CBS Sports boxing program on May 29, 2015, boxer Maureen “The Real Million Dollar Baby” Shea’s pay-per-view title bout on a Shane Mosley fight card broadcast in August 29, 2015, and the last nationally broadcast women’s bout on NBCSN, which pitted two highly popular local North East fighters Heather “The Heat” Hardy and Shelley “Shelito’s Way” Vincent for the vacant WBC international female featherweight title on August 21, 2016. This latter fight was the first female bout to be broadcast under the new upstart Premier Boxing Champions (PBC) promotion arm that has brought boxing back to broadcast television on NBC and CBS, as well as broadcasting on cable television outlets including Spike TV, NBCSN, and ESPN.

Heather Hardy (R) defeated Shelito Vincent by MD in their ten round slug fest on August 21, 2016. Photo Credit: Ed Diller, DiBella Entertainment

Four months on from the PBC broadcast, with a second Olympic cycle resulting in Claressa Shields winning her second back-to-back gold medal at the 2016 Rio Games – the first American boxer, male or female to have won that distinction – the status of women’s boxing in the United States is at a crossroads of sorts.

Since 2012, mixed-martial arts (MMA) have made significant inroads across platforms on cable, broadcast and internet-based telecasts. Moreover, this increase in visibility has come at the detriment of boxing—with more and more advertising dollars being thrown towards MMA contests. Of significance, however, has been the increasing popularity of women’s MMA (WMMA)—especially since UFC, the premier MMA league added female MMA fighters to their roster. Beginning on February 23, 2013 (UFC157), UFC began broadcasting WMMA bouts.

With the announcer declaring it a “gigantic cultural moment,” Ronda Rousey, a former bronze winning Olympian in Judo, and the Strikeforce* bantamweight WMMA champion, easily defeated her opponent Liz Carmouche with a classic “arm bar” move and in so doing, established a new first for women’s martial sports. Rousey went on to capture the imagination of country with her girl-next-door looks, winning ways, and eventual appearance in films such as The Expendables 3 and Furious 7. This catapult of a female warrior in gloves (albeit not boxing gloves) to include being only the second female fighter to ever appear on the cover of Ring Magazine (to much consternation by the boxing community), did not, however, have any particular visible effect on the fortunes of female boxing, per se,

Her first loss, however, in UFC 193 on November 15, 2015, was to a female boxer turned MMA fighter, Holly “The Preacher’s Daughter” Holm. A highly experienced female boxing champion, Holm’s boxing career of (33-3-2, 9-KOs) while very impressive, never led to the kind of breakout name recognition or big dollar paydays that should have been her due, given her talents, and caliber of many of her opponents including bouts with such boxing royalty as Christy Martin and Mia St. John (albeit later in their careers), British boxing star Jane Couch who single-handedly created women’s boxing in England, and the truly fearsome French fighter, Anne Sophie Mathis. Ensconced in her hometown of Albuquerque, New Mexico, Holm enjoyed a loyal following and excellent local coverage, and while she was a known quantity in the boxing community; it was only with her forays into MMA that she was able to break through to a larger audience and a chance at bigger paydays and television exposure.

The irony of a Rousy’s loss to a boxer was not lost on the boxing community (nor has the fact that Rousey’s recent loss in UFC207 was due to her inability to defend against her opponents unrelenting boxing “strikes”). A growing number of boxing writers who have also begun to champion the place of women in the sport with such features as Ring Magazine‘s monthly feature by Thomas Gerbasi.

November 2016 brought a flurry of attention to women’s boxing. Claressa Shields appearance on the November 19th Sergey Kovalev-Andre Ward fighting a four-rounder against former foe and USA National champion in the amateurs, Franchon Crews not only ended in a unanimous win on the cards, but the chance to see the fight live as a free streaming event. Shields has been quoted as saying, “It’s definitely a big deal, and it’s a big deal for women’s boxing, period …We really wanted a fight where we could put on a show.”

Claressa Shields delivering a straight right to Franchon Crews in their four round professional debut on November 19, 2016. Photo Credit: AP Photo/John Locher

Boxing writers and Shields herself have asked if this will be the launch point for women’s boxing—and with Claressa Shields recent appearance on the cover of Ring Magazine in celebration of her remarkable back-to-back Olympic gold medal appearances, she is certainly an important figure to be reckoned with as 2017 looms—not to mention her 77-1 boxing record in the amateurs.

Ireland’s Katie Taylor also be turned professional in England in early December, and quickly racked up to back-to-back wins with the second one also broadcast live on Showtime’s streaming online service.

Additionally, in late November, Stephen Espinoza, Executive Vice President at Showtime stated they intended to include female boxing on the network in 2017—a first since 2009. Espinoza has been flirting with the idea of putting a female bout back on the air for the last couple of years—and has paid keen interest in the success of DiBella Entertainment’s local fight cards that have included such female fighters as Amanda Serrano, Heather Hardy, and Shelito Vincent.

In an interview with The Sweet Science, Espinoza is quoted as saying; “It’s been on our to-do list for a couple of years. It’s really at its capacity. But we made a decision we are going to prioritize it.”

The first event is slated to be a WBO women’s world super bantamweight championship with the remarkably talented Amanda “The Real Deal” Serrano (30-1-1) set to fight Yazmin Rivas (35-9-1) in what promises to be a hard fought bout between two technically proficient warriors.

AIBA’s (the world international amateur boxing association) rules change just this past week may be the most far-reaching. All women’s amateur elite bouts will now be contested with in three rounds of three minutes each. The parity of the rounds and number of minutes per round is a first in the amateur world—and while elite men will still contest without helmets, there is further discussion of this otherwise controversial rules change that took effect before the Olympics in 2016.

With respect to the number of minutes per round—the normalization of the three-minute round will, in my estimation put pressure on the pros to accept this change, especially as amateurs with experience in the changed format turn professional. Given that in MMA men and women contest using the name number of rounds and same number of minutes per round, there will certainly be more impetus to push through three minute boxing rounds for women. Some states allow this already—such as New York State, but there has been reluctance to push for fights using three rounds based on the perception that women will want more money. Given the pay equity issues that already exist, there may be somewhat of a case to be made, however, with the push to three minutes, that last claim of women’s boxing being “less” than men’s because of the number of minutes in a round will be pushed aside once and for all.

Showtime’s potential entry into broadcasting female boxing along with signs that boxing sanctioning organizations are beginning to put resources into the sport led by the World Boxing Council which has now held two consecutive WBC conventions devoted solely to women’s boxing may help further propel the sport back into a more prominent place in the United States—and in place such as the United Kingdom.

Time will tell whether this actually happens, but as always, I remain hopeful!

*Strikeforce was an MMA and kickboxing league operating out of California from 1985-2013. WMMA practitioners such as Mischa Tate and Ronda Rousey were important champions and helped prove the case for televising female MMA bouts. They were particularly popular draws on Showtime. Strikeforce was bought out in 2011 by Dana White and its roster eventually folded into UFC.

Beginning with my 15 minute or so walk to the gym, I begin to destress, thinking of all the things I want to work on for that day. From “keeping it neat” to quote trainer, Don Saxby, to working the counter shots to the body that I practice on the focus pads with my trainer Lennox Blackmoore.

Beginning with my 15 minute or so walk to the gym, I begin to destress, thinking of all the things I want to work on for that day. From “keeping it neat” to quote trainer, Don Saxby, to working the counter shots to the body that I practice on the focus pads with my trainer Lennox Blackmoore.